The history of running is rich with competitions, ceremonies, and games from countless cultures across the globe. In their simplicity, foot races have been perhaps the most common athletic competition throughout history, varying between sprints of a few meters to extreme tests of endurance across vast distances. Beyond foot races, running itself, being one of the core components of general athleticism, has been a necessary component of countless athletic activities throughout history, from ancient Greek hoop rolling to medieval European mob football.

Egypt

This file is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported from Wikimedia Commons. Author: Nephiliskos

Ancient Egypt hosted a small number of foot races, typically more ceremonial in nature than competitive, although there does seem to be evidence of small, informal competitions. One such ceremonial run had held a place in Egyptian culture since its very early history – as early as 3000 BC – in a festival called heb sed, which celebrated the rule of the current pharaoh. One of the main events of this festival was a race in which only the pharaoh competed in order to demonstrate that he was still physically fit to rule. As heb sed took place 30 years into the pharaoh’s reign and every 3 years afterward, the pharaoh would be approximately 40 years old at the very youngest for his first ceremonial race.

The history of ancient Egypt does host one great competitive race without name. During the 7th century BC, Pharaoh Taharqa organized a race among several military units from Memphis (the Egyptian capital) to the Faiyum Oasis and back, with a 2 hour break halfway through. The distance totaled approximately 62 miles (100 km), nearly two and a half times the distance of the modern marathon.

Mediterranean Region

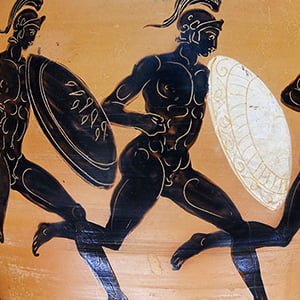

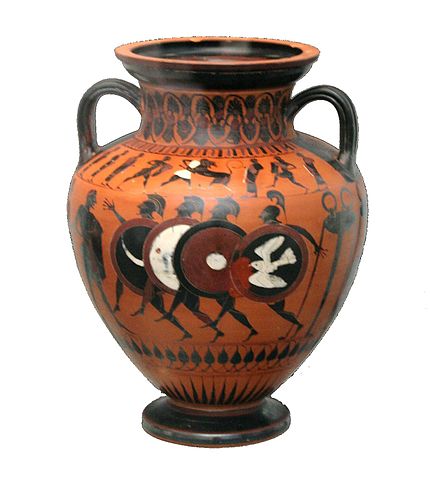

The ancient Olympic Games are typically held as the most iconic pinnacle of sportive competitions, and for the first 56 years of the festival, a footrace was its only athletic event. This race, the stadion, was a sprint of 157–196 meters (the exact distance varied among stadiums), and was regarded as the central event of the Olympic festival throughout its history. Only in 720 BC was long distance running added – a race called the dolichos. It was completed over the same track as the stadion by running from end to end until a distance of up to 5,400 meters was reached. At that time, the long distance race was not considered a main event by any means, and served more as a background event as spectators trickled in before the more exciting competitive sports. Later on in 450 BC, the festival was expanded to included the hoplitodromos, an encumbered race in which the athletes would carry various pieces of hoplite armor weighing up to 50 pounds total. This is likely the first historical record of an encumbered sprinting competition.

The full list of Greek competitions held at the Panhellenic games that consisted of or featured running is as follows:

| Event | Description |

|---|---|

| Stadion | a sprint the length of the stadion track, around 200 meters |

| Diaulos | a two stadia sprint, around 400 meters |

| Hippios | a four stadia race, around 800 meters |

| Dolichos | an endurance race of 18-24 laps on the stadion – about 3 miles |

| Hoplitodromos | an encumbered race in which athletes had to wear pieces of Hoplite armor |

| Pentathlon | a fivefold event consisting of the discus toss, javelin throw, long jump, stadion sprint, and wrestling. |

On the topic of Greek footraces, likely the most prominent example to come to mind is the Marathon. Its romanticized origin story relates that in 490 BC, a courier named Pheidippides ran a total of 153 miles (246 km) in a day and a half, first to request help from the Spartans when the Persians attacked Marathon, and then to announce their subsequent victory in Athens. The iconic 26-mile (42 km) distance from Marathon to Athens was the last leg of his journey, after which, legend relates, he collapsed and died of exhaustion. Ironically, the Marathon was never an event in the ancient Olympic Games, and has only held an official place since the new games were reignited in 1896. To commemorate Pheidippides’ entire 153 mile run, an annual race called the Spartathlon, which takes place over the same historical route, has been held in Greece since 1983.

One of the least competitive, yet most common games the Greeks engaged in was hoop rolling. While the focus of the sport wasn’t running itself, its nature necessitated that the player engage in a considerable amount of jogging. The Greeks played the game virtually identically to how one today would play it; by chasing and driving a large hoop with a short stick. The game may be regarded as somewhat childish in modern times, but for the Greeks it was an active sport, often practiced by men in the gymnasium. Horace, a 1st century BC poet, even referred to hoop rolling as a manly sport. While perhaps not the most rigorous form of training, it was a form of entertainment that would have aided in preparation for footraces and the like.

European Region

While ball sports typically demand running short distances repeatedly, no sport demanded running like that of medieval European mob football games (such as Irish caid, Welsh cnapan, and French la soule). These sports were massive in scale, with the playing field typically extending for miles across variable terrain and matches usually lasting from noon to sundown. These huge, chaotic games had players running from village to village in an effort to capture the ball and return it to a goal in their own parish. This sport required a level of running not demanded by most, and players often dropped out toward the end of the match due to fatigue and waning enthusiasm.

Though not on the same level as mob football, practically any ball sport would require a great deal of running. Field hockey sports, such as the Gaelic sport that gave way to Irish hurling and Scottish shinty, serve as relevant examples.

Ireland

The Irish Tailteann Games, founded in 1829 BC or around 1600 BC (the date is debated), serve as a record of one of running’s earliest pieces of history. The festival was held as a mourning ceremony for the death of the foster mother of Lugh, a mythological deity and king. The games were made up of an eclectic group of competitions, ranging from hurling, wrestling, and boxing to singing, goldsmithing, and storytelling. Footraces were included as well, though the distance and intensity of these races is unknown; records seem to indicate they were not a primary focus of the festival by any means. The ancient games seemed to hold warrior-related sports with higher regard, and modern attempts at reviving the games haven’t included running at all. However, this ancient festival nonetheless serves as a solid historical anchor for competitive running.

[raw_html_snippet id=”bib”]

Bard, K. A., & Shubert, S. B. (2014). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London: Routledge.

Kyle, D. G. (2007). Sport and spectacle in the ancient world. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub.

Swaddling, J. (2015). The ancient Olympic games. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Sansone, D. (2009). Ancient Greek civilization. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Miller, S. G. (2006). Ancient Greek athletics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Findling, J. E., & Pelle, K. D. (2004). Encyclopedia of the modern Olympic movement. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

König, J. (2005). Athletics and literature in the Roman empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rowley, C. (2015). The shared origins of football, rugby, and soccer. Rowman & Littlefield.

Koch, J. T. (2006). Celtic culture: A historical encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

P., & Frazer, J. G. (1913). Pausanias’s Description of Greece. London: Macmillan and, Limited.

Smith, W., Wayte, W., & Marindin, G. E. (1890). A dictionary of Greek and Roman antiquities. London: J. Murray.

Plummer, E. M. (1898). Athletics and games of the ancient Greeks. Cambridge, MA: Lombard & Caustic, Printers.

Marples, M. (1954). A history of football. London: Secker & Warburg.

Williams, G. (2007). Sport: A literary anthology. Summersdale LTD – ROW.Magoun, F. P. (1929). Football in medieval England and in Middle-English literature.

Levinson, D., & Christensen, K. (1996). Encyclopedia of World Sport: From Ancient Times to the Present. ABC-CLIO Interactive.

Nally, T. H. (1922). The Aonaċ Tailteann and the Tailteann games: Their origin, history, and ancient associations. Dublin: Talbot Press.

[raw_html_snippet id=”endbib”]