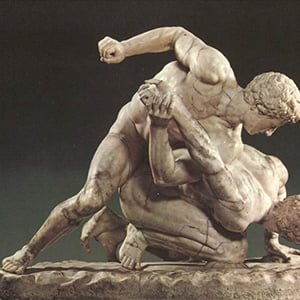

Pankration (translated from Greek as “all of might”) was a violent, unrestrained combat sport practiced in ancient Greece, consisting primarily of elements of pygmachia (boxing) and palé (wrestling). It was featured at all four of the Panhellenic festivals; the ancient Olympic Games, Isthmian Games, Pythian Games, and Nemean Games.

As there were almost no restrictions regarding combat techniques, pankration somewhat simulated no-holds-barred, bare-handed fights to the death, such as one might have encountered in war. It was considered the most dangerous of the three combat sports, and was so brutal that some athletes were known to have actually died while fighting, as was the case for pankratiast Arrhichion of Phigalia.

Origins and History

Pankration was introduced to the Olympic Games in 648 BC, though it was likely practiced for some time beforehand. It was later featured in the other three Panhellenic games as well, making it one of the only four events to be included in all four festivals. The sport enjoyed a reign of popularity for centuries, even finding a hold in Roman culture.

Pankration continued to be a featured in the Panhellenic festivals until their abolition in 394 AD under emperor Theodosius I. In the decades following his decree, all of the Panhellenic festivals slowly died out, seemingly eliminating the practice of the sport. A modern movement has resulted in a fairly small revival of the sport, though this new rendition is more regulated and less violent.

Objective

To win a pankration match, the pankratiast had to force their opponent into submission, which was indicated by raising an index finger. Knocking out or killing an opponent also counted as a win, though such victories were naturally less common. In rare cases, perhaps if the match had continued for too long, the judges would call the fight to an end and determine the winner or declare a tie. There was no time limit, so the athletes had to fight without pause until one of them submitted, was knocked out, or the judges called the match.

Restrictions

Biting and eye gouging were not allowed in pankration matches. All other methods of getting an opponent to submit were considered legal – even choking the opponent with bare hands or breaking the fingers. Violators would be struck by a referee wielding a whip or rod, without stopping the match. Fighters were likely not allowed to step out of the boundaries of the skamma, though penalties for doing so are not clear. Such absence of many regulations resulted in a sport which simulated a fight for life, in which the competitors would use whatever means necessary to overcome their opponent.

Fighting Style

A modern revival of pankration in 1969 led to the development of mixed martial arts,* and as such some similarity can be seen in the fighting styles of both sports.

The pankratiast would face forward and slightly angled to the right, with their back slightly rounded. Their hands would be held out forward at eye level, with the left a bit further than the right, both open and relaxed. Most of the athlete’s weight would be back on their right foot, with the ball of the left only touching to ground, ready to kick.

Kicking was one of the most commonly used strikes in pankration, especially kicks directly to the stomach. Bare-hand boxing strikes were used as well. Alongside striking, grappling was heavily utilized in the sport. Wrestling holds, limb locks, chokes with the hand(s) or forearm, sweeps, and takedowns were all part of the pankriatist’s repertoire.

*While the pankration revival movement did contribute to the development of mixed martial arts, pankration as a standalone sport is still practiced by some groups today.

Classes

For the majority of the sport’s history there was only one pankration class, so all fighters competed together. Though more agile and skillful pankratiasts stood a chance, the larger and stronger men naturally dominated the sport. The Olympic Games in 200 BC introduced a younger boys’ class, giving those under 18 a better chance at winning a title, though fighters were still not divided by weight. It’s likely that the other Panhellenic festivals introduced a similar classification at some point as well.

Matchmaking

Greek records indicate that matches were made through roughly the same process for all three of the Greek combat sports. At tournaments, competitors would blindly draw a lot (such as a pebble or piece of clay) with a Greek letter inscribed. Each athlete would be paired with whichever other athlete drew the matching character. If there was an odd number of competitors, someone would sit that round out. The same person could get lucky and sit out multiple rounds, however it was considered doubly honorable to compete in all rounds and win.

Major festivals, such as the Olympics, likely had four rounds with sixteen athletes. There were likely preliminary matches before major games to narrow down to that number, as records indicate some festivals had thousands of fighters vying for titles in their respective sports.

[raw_html_snippet id=”bib”]

Arvanitis, J. (2003). Pankration: The traditional Greek combat sport and modern mixed martial art. Boulder, CO: Paladin Press.

Miller, S. G. (2006). Ancient Greek athletics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Liddell, H. G., Scott, R. (2007). Liddell and Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon. Simon Wallenburg Press.

Poliakoff, M. (1995). Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, violence, and culture. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Smith, W., Wayte, W., & Marindin, G. E. (1890). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. London: J. Murray.

[raw_html_snippet id=”endbib”]