Pygmachia was an ancient Greek boxing sport featured at all four of the Panhellenic festivals; the ancient Olympic Games, Isthmian Games, Pythian Games, and Nemean Games. It was added to the Olympic Games in 688 BC, making it the 6th event and 2nd combat sport to be included in the festival. Perhaps due to its yearly presence in these four festivals, the sport maintained a high level of popularity in Greek culture for over one thousand years.

Pygmachia was the second deadliest of the three combat sports in ancient Greece, the other two being palé (wrestling) and pankration. For most of the sport’s history, fighters would wear leather gloves with sharp edges intended to cut the opponent’s face. Though not as dangerous as pankration, there were occasional fatalities during pygmachia matches.

Origins and History

Pygmachia was added to the Olympic Games at the 23rd festival in 688 BC, though it was likely practiced under this name for at least a century beforehand. There is evidence of sportive fist fighting with gloves in Crete as early as 1650 BC, but it is unclear whether this was called by the same name. The sport continued to be a featured in the Olympic Games until their abolition in 394 AD under emperor Theodosius I. In the decades following his decree, all of the Panhellenic festivals slowly died out.

Objective

The goal of the boxer was to knock his opponent unconscious or get him to submit, which was indicated by raising an index finger. There was only one round with no time limit, so a common tactic was to fatigue the opponent to elicit a submission, as opposed to aggressively pursuing a knockout.

Restrictions

Fighters were not allowed to use any wrestling holds – only strikes with the hands. Kicks and sweeps were likely not allowed, and strikes to the genitals were forbidden. Violators would be swiftly struck by a referee wielding a whip or rod, without bringing the boxing match to a halt. The boxer did not have to relent when their opponent fell, as it was within the rules to strike them while downed. Fighters were likely not allowed to step out of the boundaries of the skamma, though penalties for doing so are not clear.

Equipment

For a great period of time, fighters wore protective ox hide leather wraps called himantes around their hands, knuckles, and wrists, as well as sometimes around their chests. The sport evolved to use more dangerous, sharp-edged gloves called oxys, as well as some gloves designed to be much safer, typically used for practice and non-professional matches.

For more information, see Greek boxing equipment.

Fighting Style

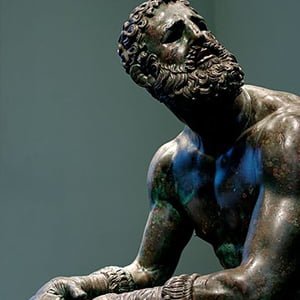

Ancient Greek depictions of pygmachia indicate that boxers in stance stood fairly erect with their body turned slightly to the right, left foot forward, and slightly more weight placed on the back foot. Their arms were held out in front, slightly bent, with hands held between chest and eye level, the left hand further out, and fists clenched or slightly open.

When striking, paintings depict the boxer would sometimes remain fairly erect as they shifted their weight to the front foot, likely in an attempt to keep their face out of their opponent’s reach. Others depict a more hunched posture during a strike, with the opposite hand held up to protect to the face.

With the introduction of oxys in the 5th century, boxers would strike their opponent’s face with the sharp-edged leather in an attempt to draw blood and inhibit their vision. (Because of tactics like this, boxers were often identifiable by their marred faces.)

Classes

Pygmachia had no weight classes – all men were expected to hold their own regardless of build and stature. As such, larger and stronger men naturally dominated the sport. With the introduction of boys’ boxing at the 41st Olympiad in 616 BC, boxers were separated by age into two classes.

Matchmaking

Records indicate matches were made through roughly the same process for all three of the major Greek combat sports. At tournaments, competitors would blindly draw a lot (such as a pebble or piece of clay) with a Greek letter inscribed. Each athlete would be paired with whichever other athlete drew the matching character. If there was an odd number of competitors, someone would sit that round out. The same person could get lucky and sit out multiple rounds, however it was considered doubly honorable to compete in all rounds and win.

Major festivals, such as the Olympic Games, likely had four rounds with sixteen athletes. There were likely preliminary matches before major games to narrow down to that number, as records indicate some festivals had thousands of fighters vying for the title in their respective sports.

[raw_html_snippet id=”bib”]

Phillips, D. J., & Pritchard, D. (2011). Sport and festival in the ancient Greek world. Swansea: The Classical Press of Wales.

Miller, S. G. (2006). Ancient Greek athletics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Newby, Z. (2006). Athletics in the ancient world. Bristol: Bristol Classical Press.

Swaddling, J. (2015). The ancient Olympic games. Austin: University of Texas Press.

[raw_html_snippet id=”endbib”]