The term “karate” sometimes refers to the general collection of Asian marital arts. This article examines the history of shotokan karate itself.

The history of karate traces back primarily to the Ryukyu Islands in modern day Okinawa, Japan, with the twisting roots of its predecessors reaching back into ancient China and India (tying in with the history of kung fu). While shotokan karate is fairly widespread today, it was predominately isolated to Okinawa before the early 20th century. There, the bulk of its developmental history took place, with evidence of martial arts on the Islands reaching as far back as the 14th century.

This article covers the chronology of the precursors to shotokan karate in China and India, its beginnings and development in Okinawa from the Middle Ages, and its dissemination from there in the 20th century.

Precursors to Karate

The early precursors to karate likely reach far back into India sometime in the first millennium AD. There is a small collection of medieval sources that credit a 5th or 6th century Buddhist monk named Bodhidharma with taking Buddhism and martial arts from India to China, establishing the first Shaolin monastery to develop Shaolin kung fu. The legend claims that the health of some of his sickly disciples improved so much that word of his teachings spread far, triggering a spread of his new martial art. However, it should be noted that this legend is no longer widely accepted. The earliest of such claims can be traced back to the 1624 exercise manual Yijin Jing (Muscle Change Classic), which makes so many literary blunders and verifiably false claims that it cannot be accepted as an accurate historical account. Regardless, it is generally accepted that kung fu developed out of Indian martial arts sometime in the mid to late first millennium AD.

The practice of kung fu and other marital arts spread throughout China over the ensuing centuries. Sometime in the 2nd millennium, perhaps as early as the 14th century, some such martial arts reached the Ryukyu Islands (modern-day Okinawa, Japan) through some means, as discussed below. From there, the history of karate in earnest began.

Origins of Karate

There are a few prominent theories regarding the origins of karate as in Okinawa, Japan, given great detail in Hutan Ashrafian’s Warrior Origins (2014) (a very detailed historical study of several martial arts). The three likely theories with the most credibility are summarized here in the order they appear in his book. (This is not a complete list of the theories given, but rather the most prominent.)

Chinese Immigrant Teaching

The Chinese immigration theory puts forth that Chinese immigrants to the Ryukyu Islands (modern-day Okinawa) taught local residents kung fu, which led to the development of karate throughout the ensuing centuries. Indeed, in 1392, thirty-six families were sent from China to modern-day Okinawa to improve trade relations between the Ming Dynasty and Ryukyu court, most of the members becoming important figures in trade between the two kingdoms. In addition to teaching natives kung fu, these families may have brought with them a variety of texts on martial arts, including the so-called “karate bible” the Bubishi, an important text in the history of karate referenced by several masters (including Gichin Funakoshi (1868–1957), discussed below).

Chinese Military Teaching

Another notable theory asserts that martial arts may have been taken to the Ryukyu Islands by members of the Chinese military. Notably, the Oshima Hikki, an 18th century historical document, recorded an incident with a Chinese military officer named Kushanku, who demonstrated an impressive level of skill in martial arts. There is evidence to suggest he was part of Emperor Sappushi’s envoys, which regularly visited the Ryukyu Islands to trade with the locals. Were this the case, it would be quite possible that these skilled guards taught these natives martial arts in the 18th century, leading to the development of shotokan karate.

Okinawan Retrieval from China

A possibility that very likely contributed to the development of karate, though to a lesser extent than the former two, is that natives of the Ryukyu Islands may have brought back martial arts after studies in China. Ashrafian’s aforementioned book gives great detail on possible figures for this theory. Notably, King Chuzan of the Ryukyu Islands sent a group of students to study martial arts in China in 1392. A very later possibility would be Ryukyu resident Higaonna Kanryō (1853–1916), who studied several branches of martial arts in China which he taught to local residents of Okinawa upon his return in the 1880s.

Development of Karate

Though the term “shotokan” refers to only one style of karate, this style developed primarily from one of three once found on the Ryukyu Islands. These styles were called shuri-te, naha-te, and tomari-te, named after the towns in which they were taught (“te” was a term meaning “karate”). Modern shotokan karate developed almost exclusively from shuri-te with a few elements of naha-te sprinkled in, though these two were at one point distinct styles with only limited crossover due to geographical proximity. (Tomari-te appears to be identical, or nearly so, to shuri-te.) There remain some masters today who attempt to practice and teach naha-te in its original, distinct form, though practice of shuri-te’s successor shotokan is much more widespread.

Shuri-Te

Shuri-te is the prominent style out of which shotokan karate developed—the primary branch in the history of karate. Historically, it placed emphasis on agility, momentum, leverage, and far-reaching attacks. The style was appropriate for the small frame of the average Okinawan native, as its techniques didn’t rely on the strength or stature of the practitioner. While it may be somewhat acceptable to refer to modern shotokan as shuri-te, it is not entirely accurate, as its founder, Gichin Funakoshi, took some liberty with the style as he developed shotokan karate (as discussed below).

Naha-Te

The naha-te style focused more heavily on controlled strength and power, and was in many ways considered the counterpart to shuri-te. Whereas shuri-te was sometimes referred to as “hard” karate, naha-te was called “soft” karate. The style was more heavy and grounded, with practitioners making use of static stances, lower centers of gravity, and closer, heavier strikes. A special emphasis was placed on being close to the opponent and keeping contact with them, granting an advantage in dark environments. Naturally, such a style appealed to large, strong men.

Tomari-Te

Tomari-te appears to have been identical (for practical purposes) to shuri-te. It is generally accepted that differentiation between the two styles serves only as clarification of the localities in which they were taught. Despite their near-indeitcality, shotokan developed out of shuri-te and not tomari-te, leaving the latter excluded it from most concise discussions of the history of karate.

Dissemination of Karate

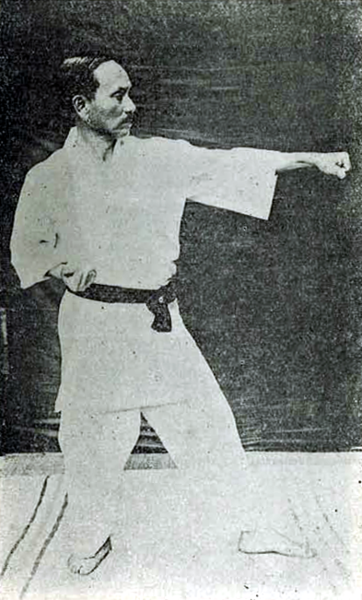

The primary figure behind the spread of shotokan karate was Gichin Funakoshi (1868–1957), a master of the shuri-te style. In Okinawa he had studied under Anko Itosu (1831–1915), often referred to as the grandfather of karate and well-known for his efforts to spread its practice. In 1901, Itosu made efforts to introduce the art to public schools in Okinawa, marking the beginning of what would become a worldwide phenomenon.

After Itosu’s passing in 1915, Funakoshi made the decision to take his master’s teachings to mainland Japan. This was during a Japanese invasion of China, so to avoid associations with the latter, Funakoshi changed the name of the art from 唐手 (“China hand”) to 空手 (“empty hand”), both pronounced “karate.” He travelled to Japan in 1917 and 1922 to demonstrate karate-do and was well-received widely. In 1936, he opened his first shotokan dojo in Tokyo, officially establishing karate’s presence on the mainland. (The name “shotokan” had developed back in Okinawa; a derivative of his pen name Shoto and the word for house or hall, kan.) In the following decades, his teachings spread across the globe, and today shotokan karate-do is practiced internationally.

[raw_html_snippet id=”bib”]

Ashrafian, H. (2014). Warrior origins: The historical and legendary links between the Bodhidharma’s Shaolin kung-fu, karate and ninjitsu. Stroud, Gloucestershire: History Press.

Clayton, B. D., PhD. (2004). Shotokan’s secret: The hidden truth behind karate’s fighting origins. Black Belt Communications.

Quast, A. (2016, April 21). On the distinction between shuri-te and tomari-te. Ryukyu Bugei 琉球武芸. Retrieved November 28, 2016. (Archived here).

[raw_html_snippet id=”endbib”]