Medieval European nutrition consisted of high levels of cereals, including barley, oats, and wheat. These were supplemented with a lot of vegetables, legumes, and a moderate amount of fruit as available in different regions throughout Europe. Meat was eaten sparingly among the lower classes and in moderate amounts among nobility due to the expenses required to domesticate animals and the effort required to hunt game. Fish served a very central role within medieval European nutrition, partially due to Catholic restrictions with regard to other meats. Overall, most classes throughout the history of medieval Europe consumed a nutritionally fulfilling diet, with the upper classes likely more prone to overconsumption than the working class.

Grains

Cereal products were a staple among all classes, making up the majority of their caloric intake. Nobility preferred to cook with wheat as it was more expensive to procure, while the lower class primarily used oats, rye, millet, and barley. These cereals usually were used to make bread that could be flavored with spices, but were also consumed in the form of porridge and, in some areas, pastas. Due to agricultural difficult in colder climates, communities throughout northern Europe didn’t consume as much bread, excluding the upper classes, who could afford to import it. Because of this, they likely had a lower carbohydrate macronutrient ratio than their neighbors to the south. Throughout all of Europe, rice was consumed very sparingly.

Fruits and Vegetables

Next to cereals, vegetables and other plant life made up the largest food group within medieval European nutrition. Carrots, onions, garlic, cabbage, and the like would all be used in stews and other dishes. Legumes such as chickpeas and fava beans were common foods as well. Chestnuts, almonds, and acorns would be consumed as available in different regions. Fruits such as apples, grapes, strawberries, pomegranates, and types of citrus were consumed as well, most of them before the main meal. Oils from plants such as olives were used in cooking, primarily in areas that could grow them.

Meat

Meat was not consumed in very high quantities. Domesticated meats such as pork and chicken were somewhat expensive, and thus eaten sparingly among the lower classes. The upper classes consumed these meats more often and hunted game as well, though consumption remained at moderate levels. Beef was rarely eaten among any class, partially because it was very expensive to raise. Goat, pork, and chicken were the primary meats available.

Fish

Fish also held a considerable position within medieval European nutrition, in part due to Catholic restrictions with regard to eating any other meat on Fridays and during certain fasts. Coastal communities consumed more marine life than their inland neighbors, though preservation techniques such as salting and smoking allowed exportation. At that point, while fish was consumed among all classes, it was more common among the upper classes, who could more easily afford it. As technological innovations allowed for more efficient trade, fish and other imported foods became more accessible.

Dairy

Dairy and other animal products were consumed in moderation. All classes enjoyed cheese, milk, eggs, and the like, except for on Fridays, when consuming animal products (excluding fish) was forbidden.

Alcohol

Alcoholic beverages such as wine, beer, and ale were consumed in considerable quantities among all classes. Catholic influences discouraged overconsumption of wine, but it seems beer was less restricted. As such, beer likely served as a fairly significant source of calories within medieval European nutrition.

Class Differences

As members of nobility had the resources to import foods and spices, their diets were distinctive from the lower class due to their access to foreign foodstuffs. Because of this, the types of food an individual ate was a greater sign of class than anything else. For example, the use of ginger, honey, or saffron would indicate an individual was quite wealthy.

However, with trade innovations lowering the cost of food importation, the lower classes were eventually able to purchase the same foods as the upper classes, and, in a sense, imitate nobility. In an effort to maintain a clear distinction among classes, laws were put in place outlining the kinds of foods members of each class were allowed to consume. This was justified with the doctrine that the stomachs of individuals within specific classes could only handle certain foods (i.e., cheap foods for lower class stomachs and finer foods for noble stomachs).

Religious Influences

Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodox Catholicism had an effect on medieval European nutrition. Most Catholics couldn’t eat animal products for nearly a third of the year – that is, throughout Lent, Advent, and on Fridays. The only exception to this rule was fish, and even this rule was bent to include all aquatic creatures and even some semi-aquatic, such as beavers.

Despite these dietary restrictions, meals throughout such periods could still be generous and filling, only consisting of a smaller pool of ingredients. Visually similar substitutes would often be consumed in place of their forbidden counterparts, such as almond milk in place of animal milk, or fish shaped to look like certain red meats. It was during fasts, when they were limited to no food or only one meal per day, that their overall caloric intake was acutely affected. This may have been beneficial, though, as modern studies have shown short-term (such as 16 hours) no-calorie fasts can result in acute health benefits (such as a temporary boost in testosterone), which with frequent repetition may have a positive impact on overall health.

Monks and other members of religious clergy were subject to stricter diets, often outlining the exact measurements of each food group they were allowed to eat. They were to abstain from all meats from hooved animals, though they often skirted this rule by labeling these foods as something other than meat. Overall, their diets were heavy with bread and beer with moderate levels of animal products. Ironically, their diets often resulted in excess caloric intake, leading to higher rates of obesity and overweightness in many monasteries.

Digestive Beliefs

With regard to medieval European nutrition, this society was under the impression that foods with certain properties had to be eaten in certain orders to properly aid digestion. The overall idea was that lighter foods needed to be eaten first, as heavier foods that supposedly took longer to digest would sink in the stomach and block the digestion of the rest, giving them time to go bad. As such, fruits and other plant life considered to be “light” would be eaten first, followed by vegetables, meats, nuts, and other foods ranked in order of “heaviness.”

In addition, every food item was considered to lie somewhere on a warm-to-cold scale and a moist-to-dry scale, in line with the theory of four humors popularized in ancient Greek medicine. Different levels of these characteristics were believed to have different effects on digestion and health, with an overall preference toward warm and moist foods.

Medieval European Nutritional Analysis

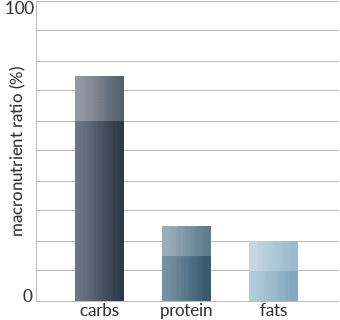

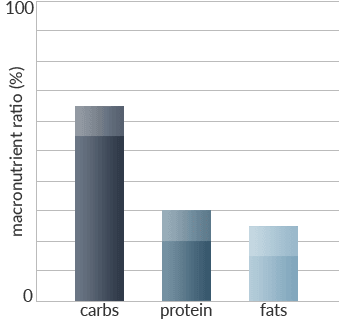

With so many socioeconomic changes throughout the Middle Ages and such wide variation in climate and class, it is difficult to assign a broad macronutrient intake ratio among European citizens of the period. All classes consumed a high percentage of carbohydrates through cereal products such as bread and porridge, as well as a fairly large quantity of beer. Meat and fish were consumed sparingly or in moderation, depending on the social class and period, with nobility eating much more red meat than the lower classes.

The lower classes, due to more modest diets and high physical activity among the laborers, likely had well-balanced nutrition without caloric excess. The upper classes, with their lavish lifestyles and physical inactivity, often consumed calories in excess, leading to fairly common obesity and overweightness. Their selection of whole foods likely did not leave them lacking in any macro- or micronutrients, however. The religious clergy, though subject to more dietary restrictions, also often consumed calories in excess, with similar macronutrient ratios as the upper class (though likely less meat).

With these things in mind, the very broad overall macronutrient intake ratio among the lower class was likely around 60-75% carbohydrates, 15-25% protein, and 10-20% fats, with little chance of caloric overconsumption.

The macronutrient intake ratio among nobility and religious clergy was likely around 55-65% carbohydrates, 20-30% protein, and 15-25% fats, with a fairly high chance of caloric overconsumption.

Medieval European Foods

Listed below are some foods that would have been commonly found within medieval European nutrition, organized roughly by food group.

Cereals

- Barley

- Millet

- Oats

- Rye

- Wheat

Fruit, Vegetables, and Legumes

- Acorns

- Almonds

- Beans

- Carrots

- Chestnuts

- Garlic

- Grapes

- Lemons

- Lentils

- Limes

- Olives

- Onions

- Oranges

- Pomegranates

- Squash

Meat and Fish

- Chicken

- Cod

- Goat

- Goose

- Herring

- Pork

- Roe

- Sauerkraut

Dairy and Animal Products

- Cheese

- Milk

[raw_html_snippet id=”bib”]

Adamson, M. W. (2004). Food in medieval times. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Carlin, M., & Rosenthal, J. T. (2003). Food and eating in medieval Europe. Bloomsbury Academic.

Dyer, C. (2003). Everyday life in medieval England. Bloomsbury Academic.

Winter, J. M. (2007). Spices and comfits: Collected papers on medieval food. Totnes: Prospect Books.

Scully, T. (1995). The art of cookery in the Middle Ages. BOYE6.

Adamson, M. W. (1995). Food in the Middle Ages: A book of essays. New York: Garland Pub.

Fenton, A., & Kisbán, E. (1986). Food in change: Eating habits from the Middle Ages to the present day. Edinburgh: J. Donald in association with the National Museums of Scotland.

[raw_html_snippet id=”endbib”]