There are many subsets of yoga with various levels of focus on physical, mental, and spiritual aspects. This article focuses on the history of hatha yoga (in addition to relevant context of the history of yoga in general), as this form is the most relevant to the history of health and fitness and is perhaps the most widely practiced form of yoga today. (The term “yoga” usually refers to hatha yoga.)

While the most common forms of yoga today typically focus on exercise and physical control, the history of yoga has consisted predominantly of practices focusing on the mental, conscious, and spiritual (typically within Buddhist or Hindu philosophies). Even the earliest texts that reference yoga and its precursors, such as the Katha Upanishad, Shvetashvatara Upanishad, and Maitrayaniya Upanishad (all 1st millennium BC religious/meditative texts), focus primarily on meditation, quiescence, breathing, inward focus, and the like. A study of the history of yoga as a means of health and fitness necessitates looking closer to modern history, as its early roots don’t have such a focus.

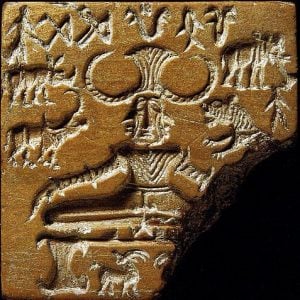

In addition, the early roots of yoga as a whole are difficult to identify. In discussing the history of yoga, many sources trace its origins back to the Indus Valley between the 27th and 20th centuries BC, based primarily on a small set of soapstone seals that seem to depict figures in yogic positions. The most often referenced of these is displayed to the right, depicting a figure with crossed legs and hands resting on the knees, a common posture for meditative yoga in modern times. However, there is some debate over whether such an image alone is enough to prove the presence of yoga in this region and period, as cross-legged sitting is a fairly natural position that does not necessitate such a link. In the absence of strong evidence of yoga (with regard to either mental or physical exercise) in the Indus Valley during this period, this claim is suspect.

Over the ensuing millennia, a variety of religious and meditative texts in the Eastern World developed the practice of yoga in its many forms, with variations in form and philosophy among different yogi (practitioners and teachers). Only toward the beginning of the 20th century did hatha yoga in its popular, modern form begin to culminate.

Early Hatha Yoga

Hatha yoga, dating as far back as the 11th century AD, has historically had a focus on mental and physical strength (as opposed to the mostly spiritual focus of other branches). There are three Hindu texts from the Middle Ages that are primarily responsible for the development of haha yoga; Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā (15th century), Shiva Samhita (sometime before the 16th century), and Gheranda Samhita (17th century). These texts give instruction on posture, positions, meditation, tantras, breathing, and the like, and were used to systemize and teach hatha yoga for centuries.

The lack of hatha yoga texts in the ensuing few centuries suggests its practice declined to some degree during this period. Indeed, before the 20th century, hatha yoga was rarely practiced and was considered a fairly obscure subset. The master yogi Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (1888–1989) studied this branch, even publishing essays on the three medieval texts referenced above. It was directly through his efforts that hatha yoga was revitalized, and through his students that it became a worldwide practice.

Krishnamacharya and Modern Hatha Yoga

Tirumalai Krishnamacharya is widely considered the father of modern yoga, having brought about a revival of hatha yoga as a form of physical exercise. Krishnamacharya taught hatha yoga, which was quite obscure at the time, at lectures all over India, bringing about a huge resurgence of hatha with a greater focus on its physical benefits. A few of his students, including his son T. K. V. Desikachar, took his teachings overseas, and swiftly ignited a spark of international interest. These students introduced and popularized other aspects of hatha yoga that are now commonplace, such as the use of props. By the mid-20th century, hatha yoga had become a fashionable form of exercise throughout much of North America and Europe.

It is through Krishnamacharya that yoga had a resurgence in the 20th century, and through a filter of his teachings that most Westerners view yoga – that is, with a focus on its physical benefits rather than the mental or spiritual. While the mental and spiritual aspects of hatha yoga are still respected, they are more removed from the practice than they had been throughout most of the history of yoga. Through Krishnamacharya’s efforts, this meditative workout is now practiced worldwide.

[raw_html_snippet id=”bib”]

Samuel, G. (2008). The origins of yoga and tantra: Indic religions to the thirteenth century. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Goldberg, E. (2016). The path of modern yoga: The history of an embodied spiritual practice. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions.

Mohan, A. G., & Mohan, G. (2010). Krishnamacharya: His life and teachings. Boston: Shambhala.

Burley, M. (2000). Hatha-Yoga: Its context, theory, and practice. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

[raw_html_snippet id=”endbib”]