This article looks at medieval Irish nutrition before the introduction and widespread incorporation of the potato in the 16th and 17th centuries.

This file is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported from Wikimedia Commons. Author: Notafly

Medieval Irish nutrition revolved heavily around dairy and meat, followed by a hearty portion of grains and vegetables. Though fruits were somewhat underrepresented, the average Irish diet throughout the Middle Ages was likely fairly well-rounded, perhaps only lacking slightly in carbohydrates by modern recommendations.

The foods represented in ancient and medieval Irish nutrition were primarily acquired through a combination of domestication, hunting-gathering, and agriculture. As dairy played a very central role in the Irish diet, domestication of cows was essential. In addition, because of the importance of milk, beef was typically supplied only by bulls and old females. Pork made up the majority of consumed meat, supplemented by the availability of game. The plant life used in Irish cooking was subject to the seasonal availability of their crops; for example, the yearly harvest of oats toward the end of summer.

The cauldron was the staple cooking tool in ancient and medieval Ireland. These large pots, typically made of bronze, were used to make endless variations of soups based on the availability of ingredients. All sorts of meats, fish, vegetables, and grains would be mixed together to make hearty stews, often complimented with barley or oat bread. These same cauldrons were used as crude ovens as well, sometimes turned upside-down on hot stones to bake bread. In the absence of cauldrons, cooks would use spit roasts, open fires, or troughs of water brought to a boil by fire-heated stones.

Food Groups

Dairy

This file is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported from Wikimedia Commons. Author: Bazonka

Dairy played perhaps the largest role in medieval Irish nutrition. In addition to its use in cooking, cow milk would be thickened to form a variety of beverages, from fresh milk to buttermilk to nearly-solid milk. It was often boiled with seaweed and mixed with honey to produce a sweet, thickened dessert as well. Milk curdles were a common delicacy, so popular that they were often referred to as “whitemeats.” After the curdles were collected from the aged milk, the leftover milky liquid was sometimes given to slaves as a lower-quality beverage of sustenance.

Butter was another staple dairy product. Though it was not eaten plain like milk was, it was mixed into quite a few dishes. It could be seasoned with salt and herbs and mixed with most grain-based products, such as porridge and bread. Though it was often salted to help prevent rancidity, rancid butter was used in cooking as well. A mixture of rancid butter and water was used to boil meats in on occasion, and sometimes rancid butter was stored in buried barrels to make “bog butter.”

Grains

Though not as highly celebrated as milk, grains likely made up the next greatest portion of medieval Irish nutrition. Barley and oats were represented in abundance; porridges, gruel, bread, scones, and grainy drinks were all a part of the Irish diet. These grains could be mixed into other dishes as well, such as soups and stews. Though wheat and rye were available, they were difficult to grow in the cold climate, so they were generally reserved for nobility. It was a sign of wealth to be able to eat full wheat bread due to its scarcity.

Meat and Fish

Medieval Irish nutrition incorporated a lot of meat – pork and beef, mostly, though goat, venison, and game all found a place at the table on occasion. These meats were usually spit roasted, boiled, or mixed into a stew. Chicken, another fairly common meat, was typically cooked by coating the un-plucked bird in clay and throwing it in the fire. When the clay hardened, it could be cracked open, pulling off the feathers and skin to reveal the cooked fowl underneath.

Though perhaps off-putting to many readers, blood pudding was a fairly common dish during the colder months when meat was more difficult to come by. A small amount of blood would be drained from the neck of a cow so as not to kill it, and this blood would be dried or salted. Throughout the winter, this substance could be rehydrated to make a protein-rich pudding.

Fishing was fairly common in Medieval Ireland as well, bringing a steady stream of salmon, pike, trout, and perch to the table. Coastal communities had access to a variety of shellfish with which they flavored their soups; crabs, shrimp, clams, and oysters were all fairly commonplace is these dishes. Cooks would throw seaweed, vegetables, and herbs in with these fresh catches to make hearty stews.

Fruits and Vegetables

Prior to the 8th century, agriculture didn’t account for much of medieval Irish nutrition. Most of the plant life incorporated into the Irish diet came from gathering, though there appear to have been a few exceptions; for example, in the planting of apple trees. The Irish had access to a few leafy vegetables such as watercress, a couple varieties of hearty vegetables like onions, and a fairly wide selection of berries.

With the spread of agricultural production in Ireland after the 8th century, varieties of celery, garlic, carrots, and onions were incorporated into Irish dishes far and wide. With the increasing Norman influence around the 12th century came the introduction of a few other vegetable breeds, such as beans and peas. Despite this increase in agriculture, it appears that fruits were not grown nearly as commonly as vegetables, reserved primarily for desserts and treats.

Alcohol

There were a few types of alcoholic drinks that found a place medieval Irish nutrition. One of the most popular was metheglin, a type of fermented honey mead flavored with sweetbriar, thyme, and rosemary. Spiced ale made from fermented corn was fairly popular, though not as much as metheglin. Wine, although not as common as in ancient Greek and Roman diets, was fairly commonplace as well. Sloe wine, one the most popular alcoholic beverages, was made by mixing mashed sloe berries with honey and water and fermenting the concoction in barrels underground.

Despite modern Irish reputation, there are a few pieces of evidence that suggest that the medieval Irish people were fairly temperate in their alcoholic consumption. For example, during great feasts, where one might expect large amounts of alcohol to be consumed, each table would often share one cup, limiting the amount of alcohol each individual could drink. To further suggest such a level of moderation, Brehon Law (Irish legal codes in effect from approximately the 7th to 17th centures) forbade men from becoming excessively overweight or developing pot bellies, something we would expect to be commonplace in a culture of high alcoholic consumption.

Variation in Diet Throughout History

Prior to the 3rd century AD, agricultural productivity rose and fell in waves of about 200 years. Archaeological evidence shows that forests would be cleared for agricultural production for a period of time, then these forests would regrow within a few centuries as the people turned to hunting and gathering again. This appears to have continued cyclically for some time until the 3rd century AD, after which there was a permanent expansion of agriculture

Famines and plagues ran through the country on occasion, wiping out animals and crops. During such times, food was naturally scarce, and some families even sold their children to afford food. Some literature reveals that in long-extended famines, families would sometimes resort to cannibalism and eating dogs. Naturally, such practices were considered abnormal, and would not represent the average Irish diet during this period.

Medieval Irish nutrition underwent a great change under Norman rule from the 12th century onward. This new power enforced restrictions on hunting and fishing, engaged in deforestation for fuel and materials, and gave sections of land to a large number of Scottish and British soldiers as payment for military services. With the increase in population and divvying of land, the introduction of the potato to Ireland in the 17th century proved to be a necessary factor to help the natives make it through the increasingly nutritionally scant winters. Even though this diet was not preferred at the time to traditional Irish cuisine, it was widely accepted as necessary by the late 17th century. By the 18th century, this starchy vegetable was considered an Irish staple.

Medieval Irish Nutritional Analysis

Based on the evident diet of medieval Ireland, the average Irish citizen was likely quite nutritionally healthy. Total calories consumed likely came from dairy mostly, then meat and grains fairly equally, followed by plant life. This may have resulted in a slight overrepresentation in fats due to the high consumption of dairy and meats.

Based on the evident diet of medieval Ireland, the average Irish citizen was likely quite nutritionally healthy. Total calories consumed likely came from dairy mostly, then meat and grains fairly equally, followed by plant life. This may have resulted in a slight overrepresentation in fats due to the high consumption of dairy and meats.

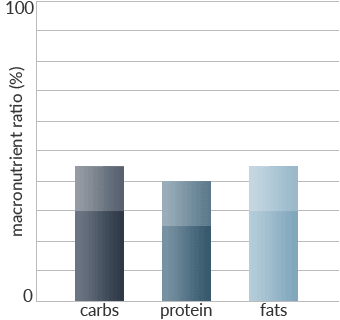

Bearing these factors in mind, the macronutrient ratio for the average Irish citizen throughout most of the medieval ages (not during times of famine) would likely have been around 30-45% carbohydrates, 25-40% protein, and 30-45% fats. Though perhaps slightly macronutrient-imbalanced with regard to modern recommendations, the presence of diverse, whole foods in medieval Irish nutrition would have left the average citizen fairly healthy.

Medieval Irish Foods

Listed below are some foods that would have been commonly found in the medieval Irish citizen’s diet, organized roughly by food group.

Grains

- Barley/oats mixed into stew

- Bread (barley/oat)

- Porridge and gruel (barley/oat)

- Wheat scones (among the wealthy)

Fruit, Vegetables, and Legumes

- Apples

- Beans

- Blackberries

- Carrots

- Celery

- Cherries

- Chives

- Hazelnuts

- Leeks

- Onions (several varieties)

- Peas

- Strawberries

- Watercress

Meat and Fish

- Beef

- Chicken and other fowl

- Clams

- Crab

- Goat

- Hare

- Hedgehog

- Oysters

- Pork

- Salmon

- Shrimp

- Trout

- Tuna

- Venison

Dairy, Eggs, and Oils

- Eggs: duck, goose, chicken

- Butter (many varieties)

- Cheeses (many varieties)

- Curds (many varieties)

- Milk (many varieties)

[raw_html_snippet id=”bib”]

Davidson, A. (2014). The Oxford companion to food. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Flavin, S. (2014). Consumption and culture in sixteenth-century Ireland: saffron, stockings and silk. The Boydell Press.

Linnane, J., BSc, MSc. (2000, February 19). A History of Irish Cuisine (Before and After the Potato). Ravensgard.

[raw_html_snippet id=”endbib”]