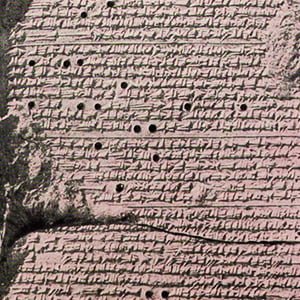

Ancient Babylonian medicine is a term that refers to healthcare practices and beliefs in ancient Babylonian culture. Medicine in ancient Babylonia revolved heavily around magic, with little scientific process aside from diagnoses and prognoses – though even these processes were saturated with supernaturalism (much like within ancient Egyptian medicine). Overall, Babylonian healthcare relied on magic and incantations as much as, if not more than, natural treatment and prescriptions. This information is revealed primarily through Assyrian copies of Babylonian texts thought to originate in the first half of the 2nd millennium BC.

Though these Babylonian physicians recorded a great number of prescriptions, most of their ingredients are considered today to be ineffective for the conditions in question. Most of the materials used were likely chosen based on a combination of trial and error with guesswork. Examples of such prescriptions are given under Medicine below.

In addition to the guesswork, part of the reason most of these prescriptions weren’t very effective is that Babylonian physicians weren’t aware of the functions of most of the components of the body. While dissections did reveal to them the location and appearance of many organs, their understanding of most of them only went so far. In fact, they were under the impression that the liver served as the life source of the body, both physically and spiritually. Within songs and poetry, Babylonians would even use the word “liver” where modern Westerners might use the word “heart.”

Diagnoses and Prognoses

Archaeological records indicate that practitioners of ancient Babylonian medicine attempted to diagnose and treat a wide variety of ailments, including intestinal disorders, respiratory issues, urinary problems, epilepsy, and various mental disorders. However, their diagnoses didn’t always propose natural causes for these ailments. Oftentimes they would attribute afflictions to gods or spirits, looking to astrology and other superstitious methods for a prognoses and treatment. For example, the author of the 11th century BC Diagnostic Handbook (Sakikkū), the most complete Babylonian medical text, wrote that if a physician were to sight a pig on his way to see a patient, the kind of pig would be an indication as to the patient’s outcome. The writer put forth that spotting a black pig was a sign of an extreme condition or certain death while a white pig was a sign of a likely recovery, offering explanations for other colors as well.

Another section of the text lists symptoms related to kidney disease, including black urine, urine like wine, and urine like water, offering a prognosis for each. For each of these, the author suggests, in order, “he will die,” “his illness will be severe, then he will recover,” and “his illness will last long, but he will recover.” Similar prognoses relating to great number of ailments can be found in numerous texts detailing ancient Babylonian medicine.

Practitioners

Babylonian healthcare was managed primarily by two types of practitioners: the physician and the exorcist (or priest). The two of them worked together to provide patients with both medical treatment and protection from evil spirits which were believed to negatively affect health.

The physician primarily dealt with diagnoses, prognoses, and physical treatment, including prescriptions and their administration, wound care, surgeries, and the like. No certification or proof of knowledge was required, however, so anyone could claim to be a doctor and begin practicing medicine. While the practitioner of Babylonian medicine would often ascribe non-superficial ailments to the supernatural, magical remedies were typically the specialty of the exorcist.

The exorcist’s primary role within ancient Babylonian medicine and healthcare was to exorcise evil spirits thought to contribute to many ailments, protecting the patient from further harm. They were well-versed in magic incantations to be recited alone or alongside medical treatment, a few of which are detailed under Magic and Spiritualism further down. Typically, psychological issues were thought to be caused by demons, and as such the exorcist usually had a bigger role in treating mental disorders than did the physician. However, the exorcist did sometimes act as a physician, providing diagnoses, prognoses, and natural treatment in tandem with the supernatural.

It is not to be misunderstood that the physician and exorcist were symbolic figures of a battle between logical, empirical science versus supernaturalism. They held the same beliefs with regard to medicine, and their roles often overlapped. Between the two, the exorcist was held with higher regard, as he had higher social standing and recognition due to his religious importance. His position was not easily attainable, while, in contrast, anyone could become a physician, provided they could gather the resources to start producing drugs.

Medicine

Ancient Babylonian medicine made use of a great number of materials – primarily plant life and animal products (sometimes feces), along with minerals. Many of the materials used in these prescriptions remain unidentified. These ingredients could be administered in several forms, including salves, rubbing oils, drinks, pills, wraps, and enemas. No evidence indicates the use of any of these materials in anesthetics, however (which, as a side note, would mean any patient undergoing surgery would have to endure high levels of pain). In addition, while mental disorders were primarily treated with magic, physicians also made use of herbal remedies.

Some texts detail prescriptions for a salve to help “sun disease,” which was likely sunburn. One document details treating kidney problems by inserting a bronze tube in the urethra and blowing drugs through. Below is another prescription for kidney disease from a Babylonian medical text. (The unknown materials are anglicized and left untranslated.)

Crush together imhur-lim, myrrh, ostrich eggshell, black frit – for 3 days in fish brine, for 3 days in drawn wine, and for 3 days in pomegranate juice – he keeps drinking it and he will improve.

The following is a prescription intended to treat intestinal bloating and flatulence:

Heat in premium beer nlnu, mountain plant, hasu, nuhurtu, juniper, kukru, sumlalu, ballukku, cuttings of aromatics, field-clod, plants – filter and cool them, add oil into the mixture – pour it into his anus and he will recover.

Magic and Spiritualism

Magic played a central role in ancient Babylonian medicine, with both the exorcist and the physician utilizing the supernatural to a large degree. Even natural medical treatment would typically be administered alongside some sort of spell or incantation. For example, below is an incantation warning debris to leave the eye before the physician intervenes to remove it himself.

Eyes with the porous blood vessel, why have you been blurred by chaff, thorns, sursurru-irait, or river algae?

Why have you been blurred by clods in the streets or twigs in crevices?

Rain down here like a star, keep falling here like a meteor, before the knife and scalpel of Gula reach you.

– An irreversible incantation, the incantation of Asalluhi-Marduk and the incantation of Ningirimma, master of spells, and Gula, master of healing arts, has cast it and I have taken it up.

Note the references to Gula, the goddess of healing. She is often referred to in magical incantations used in the spiritual aspects of ancient Babylonian medicine. However, these spells are more than just appeals to gods and spirits. They were actually a form of prose (unstructured poetry), often using symbolic language and repeating motifs. For example, in the incantation above, the exorcist calls for the debris (or perhaps tears) to rain down like a [shooting] star. Other common elements used by writers include repetition and short stories, as seen in the following incantation regarding a sore in the eye:

The wind was blowing in heaven and a sore settled in a man’s eye.

It blew in from the distant heavens and a sore settled in a man’s eye.

A sore was found in the sick eyes.

The eyes of that man are troubled – his eyes are blurred, and when by himself, that man cries bitterly.

Nammu noticed that man’s illness:

“Take crushed kasu, recite the Eridu incantation, bind the eye of that man.”

When Nammu touches the man’s eye with her pure hand, may the wind which is swept into a man’s eye be removed from his eye.

Standardization

The Babylonian healhcare system seems to have been fairly well standardized, subject to some level of legal code. The Hammurabi Code (c. 2000 BC), inscribed on an 8-foot tall block of black diorite, covers doctor payment and malpractice. Lines 218 to 221, listed below, detail punishment for malpractice as well as proper payment for physicians:

- If the doctor has treated a man for a severe wound with lances of bronze and has caused the man to die, or has opened an abscess of the eye for a man and has caused the loss of the man’s eye, one shall cut off his hands.

- If a doctor has treated the severe wound of a slave of a poor man with a bronze lances and has caused his death, he shall render slave for slave.

- If he has opened his abscess with a bronze lances and has made him lose his eye, he shall pay money, half his price.

- If a doctor has cured the shattered limb of a gentleman, or has cured the diseased bowel, the patient shall give five shekels of silver to the doctor.

These lines and others inscribed on the block indicate a widespread, fairly standardized system of healthcare throughout ancient Babylonia.

[raw_html_snippet id=”bib”]

Harper, R. F. (2013). The code of Hammurabi, king of Babylon about 2250 B.C. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Geller, M. J. (2010). Ancient Babylonian medicine: Theory and practice. Chichester, West Sussex, U.K.: Wiley-Blackwell.

Oppenheim, A. L., & Reiner, E. (1977). Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a dead civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Biggs, R. D. (2005). Medicine, surgery, and public health in ancient Mesopotamia. Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies, 19.

Horstmanshoff, H. F. L., Stol, M., & Tilburg, C. R. (2004). Magic and rationality in ancient Near Eastern and Graeco-Roman medicine. Leiden: Brill.

[raw_html_snippet id=”endbib”]